Explore the rich history of the Tahoe Basin with its many myths and legends

Stephen-Townsend-Murphy Party

The colorful history of Truckee dates back to 1894, when the Stephen-Townsend-Murphy party was migrating west, trying to cross the Sierra before winter set in. A friendly Paiute Indian offered assistance in guiding the party to California. His name sounded like "Tro-kay" to the white men, who dubbed him "Truckee". Truckee became a favorite of the white settlers after finding his intentions to be honest and true. Truckee was an Indian Chief and the father of Winnemucca. The party reached the lower crossing of a river near what is now Wadsworth and named it the Truckee River. Captain Stephen of the Party, discovered Donner Lake. It was called Truckee’s Lake in 1846 when the ill-fated Donner Party camped there. The Donner Party was part of a great western migration that began in 1846. The Donner Party reached this area in October 1846, and their tragic fate, combined with its tenacious pioneer spirit, is commemorated at their campsite at what is now Donner State Park.

In 1868, the Central Pacific Railroad was built through Truckee as part of the transcontinental railroad; the line remains a vital part of the town today. The building of the railroad created what was then known as the "second-largest Chinatown" on the Pacific Coast. Although essential to the railroad construction, the Chinese were never assimilated into the town, and Chinatown was burned at least four times. In 1879, after the last burning, tensions were near the breaking point and the Chinese began to arm themselves. They were prevented from rebuilding on their previous site and were forcefully "persuaded" to build across the south side of the river. Tensions eased until the 1880's, when the American Workingmen's movement coalesced under the slogan "'The Chinese must go". The Chinese, who had played such a key role in railroad construction, threatened to monopolize the local logging industry. In early 1886, the white citizens of Truckee banded together to rid the town of the Chinese. Within nine weeks, the industrious Chinese had been completely driven from the community, so thoroughly that for generations no Chinese would be found in or near Truckee.

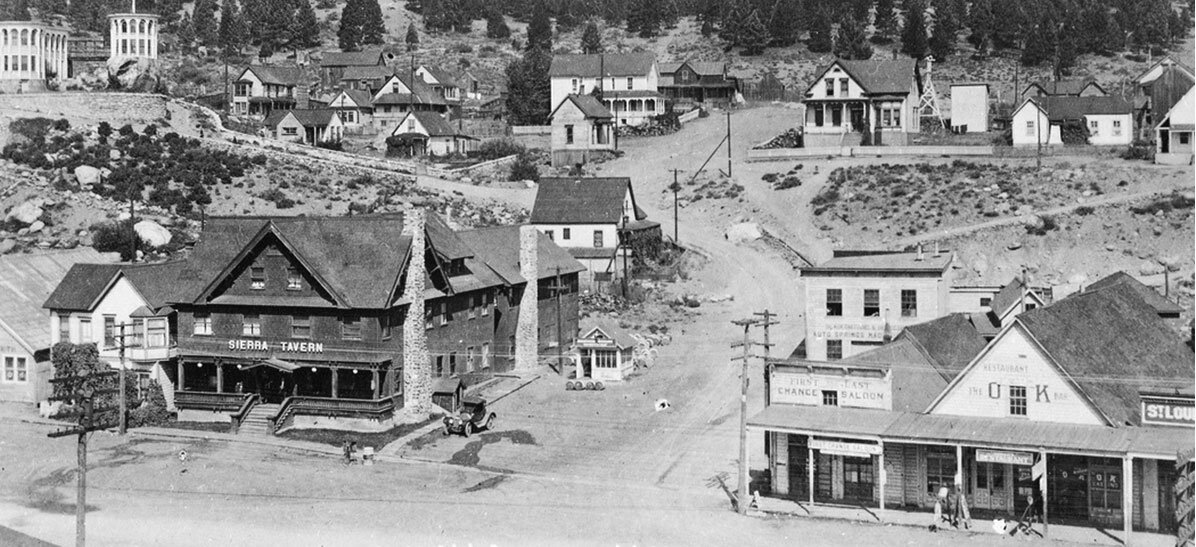

Logging has been a key industry in Truckee over the past century, along with the railroad. In the late 1800's, the town gained a reputation as a wild Old West town, with plenty of saloons and a red-light district. After the 1920's, Truckee began a 40-year period of little growth and development, particularly during and after the War years. Finally in 1960, the Winter Olympics were held at Squaw Valley, putting the Truckee-Tahoe area on the map as a major destination resort for year-round recreation. Tourism has become the town's largest industry. An active group of citizens have preserved much of the original architecture of Truckee. The town has also retained its down home friendliness, unique close community along with its Western charm.

The queen of the Washoe Indian Basket Weavers, Dat So La Lee made hundreds of baskets.

Known by many names — her birth name, dabuda; her nickname, dat so la lee; her anglo married name, Louisa Keyser — she, by any moniker, is considered the queen of the Washoe Indian Basket Weavers.

Born in the 1820s or ’30s near what would become the mining town of Sheridan in Carson Valley, Nevada, Keyser belonged to the southern Washoe, a tribe known for basketmaking. She would take the traditional art to a new level, painstakingly crafting sculptural coiled willow baskets of such skill and aesthetic innovation that they would one day fetch six figures and be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In her early years, Keyser did laundry and cooked for miners and their wives. Then she met Carson Valley entrepreneur Abe Cohn, who hired her to weave baskets exclusively for him to sell at his Emporium in Carson. Sponsor, manager, and agent, he gave her the name Dat So La Lee, “Queen of the Basketmakers.” Although Cohn kept most of the money from the baskets, their 30-year arrangement allowed Keyser to weave full time.

She died in 1925, having made hundreds of baskets. “She was among the last of those Washoe weavers whose ancient art had been practiced by countless generations,” wrote Esther Summerfield for the Nevada State Historical Society. “Her memories and her visions are beautifully woven into her baskets and will live on to remind us of the history and unique tribal artistry of her people, the Washoe Indians.”

Traditionally, Washoe utilitarian baskets, or degikup, were round, watertight baskets made to hold such things as acorn mush, pine nut soup, and a drink made from wild rhubarb. Degikup were also important in Washoe ceremonies. During the Washoe girls’ dance, food was put in degikup and given to singers in thanks for their singing; another degikup was thrown out to the dancers as a gift. These baskets were relatively simple in form and design—as were Dat so la lee’s first baskets. However, Dat so la lee transformed the shape and design of degikup, making truly aesthetic, sculptured baskets.

The basket with the hourglass design, somewhat unusual for a Dat so la lee basket because of its widely flared mouth, was made with willow foundation rods and thread. The hourglass design is woven with dyed bracken root, and the interior bear-paw motif is woven with redbud. Willows were found along the main watercourses in Washoe country, especially along the Carson River where Dat so la lee lived. The red branches (western redbud) used for the bear-paw motif were found in traditional Washoe lands along the hillsides in Woodfords Canyon and Lake Tahoe, and in Miwok country and other places along the western border of the California Sierras. The bracken-fern root used for the hourglass had to be dug up and dyed in dark mud before being woven in the basket design.

The basket with the bracken root woven into vertical columns is more typical of Dat so la lee’s work. It incorporates a more traditional design repeated around the basket.

A Tragic Tale: The Donner Party

The Donner Party is the name given to a group of emigrants, who became trapped in the Sierra Nevada mountains during the winter of 1846-47. Nearly half of the party died, and some resorted to eating their dead in an effort to survive. The experience has become legendary as the most spectacular episode in the record of Western migration. Like many thousands before them, the Donners had every reason to look forward to their journey when they started out from Springfield, Illinois, in April of 1846. Countless wagon trains made the 2000-mile trek from Illinois to Oregon and California in the 1840s. Among the multitude of emigrants bound for opportunity in California, were three well-to-do families from Springfield, Illinois: brothers George and Jacob Donner and their wives and 12 young children, and James and Margaret Reed and their four children. Gold had not yet been discovered; these families were moving to California to build community and a personal future.

The first part of the journey was a pleasant adventure for the Donners and Reeds, particularly be- cause they were wealthy enough to hire young men in Illinois to travel with them and do the heavy work. George’s wife, Tamsen, was writing a book about the trip (sadly, neither she nor her manuscript was destined to survive) and intended to open a school in California. As the summer wore on, their leisurely pace placed them near the end of the long line of wagons heading for California. The Donners would not reach the Sierras until the end of October. This fateful decision cost them dearly in time, livestock, and equipment. The emigrants arrived at the eastern base of the Sierra exhausted, demoralized, bitter, harassed by Paiute Indians, and out of food. Fortunately, Charles Stanton, a bachelor who had gone ahead to obtain provisions, arrived from Sutter’s Fort (Sacramento) with seven pack mules laden with provisions, and news of a war brew- ing in California between the U.S. and Mexico. The most difficult portion of the journey was crossing the Sierra, so the emigrants rested for five days in Truckee Meadows (Reno). Once in the mountains, George Donner cut his hand while repairing a broken wagon axle at Alder Creek, six miles north of Truckee’s Lake (now called Donner Lake). George, in his sixties and exhausted from the strenuous journey, decided to stop with his buddies and their families there and wait for rescue in California.

By the time the rest of the party reached Truckee’s Lake at the end of October, several feet of snow blanketed the pass. Snowstorms swept the Sierra during November, trapping the 87 pioneers for the winter with insufficient food and supplies. Relief was fatally slow coming for the Donner Party. In fact, it was only after a few of the pioneers managed to snowshoe over the mountains and down to the Sacramento Valley to get help, that word of the emigrants tragic predicament reached the settlements. By the time they arrived, many members of the group had starved to death and others had survived only by resorting to cannibalism. In total, of the 87 men, women and children in the Donner party, 46 survived, 41 died. George Donner and his wife died at the camp, along with his brother Jacob and Jacob's wife, and most of the Donner children. James Reed, having safely reached Sutter's fort, led one of the rescue par- ties. Reed's family survived. The story of the Donner tragedy quickly spread across the country. Newspapers printed letters and diaries, along with wild tales of men and women who had gone mad eating human flesh. Emigration to California fell off sharply and Hastings' cutoff was all but abandoned. Then, in January 1848, gold was discovered in John Sutter's creek. By late 1849 more than 100,000 people had rushed to California to dig and sift near the streams and canyons where the Donner party had suffered so much. In 1850 California entered the union as the 31st state. Year by year, traffic over "Donner Pass" increased. Truckee Lake became a tourist attraction and the terrible ordeals of the Donner party passed into history and legend.

Sarah Winnemucca, Paiute Princess and Indian Activist

The compelling story of Sarah Winnemucca and her devotion to protecting the Paiute Tribe is a poignant tale of an old culture caught in the turbulence of a rapidly changing world. The United States’ 1848 victory in the Mexican-American War and the virtually simultaneous discovery of gold in California initiated an invasion of miners, surveyors, prospectors, settlers, businessmen and land speculators into the American West. Indigenous tribal populations were quickly marginalized or eliminated. Winnemucca, granddaughter of Chief Truckee, became the leading activist and passionate spokeswoman who informed the public and politicians about the cruel injustices being imposed on native peoples in the West.

Although overshadowed by commercially popular Native American women such as Pocahontas and Sacajawea, whose names are well known among the general public, historians consider Winnemucca one of the most notable women in 19th Century America. Commemorative statues honor her achievements in both Washington D.C., and Carson City, the capital of Nevada. Blessed with insightful intelligence and graceful fluency in the English language, Winnemucca marshalled formidable communication skills along with eloquent public speaking to spearhead an advocacy movement for the Paiute Nation. The federal government reacted slowly, but Winnemucca’s impassioned lectures stirred wealthy audiences on both coasts to donate generously to her cause.

At hundreds of presentations around the country, Winnemucca spoke extemporaneously without notes and rarely repeated herself. In the process she charmed and educated her audience while she pled for fair treatment for the Paiutes. She asked that her people be allowed to preserve their own culture, not be forced into Christianity and be given land for a permanent home. Winnemucca’s reputation as an activist enabled her to meet American presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester A. Arthur, along with other top federal officials. When Winnemucca petitioned President Arthur’s administration for help, none was forthcoming, but it spurred the U.S. Congress to listen to her.

In April 1884, Winnemucca testified before the House Sub-Committee for Indian Affairs where she criticized flawed government policies and castigated corrupt agents working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs who withheld food, clothing and provisions from the tribes. She said, “You take the nations of the earth to your bosom but the poor Indian … who has lived for generations on the land which the good God has given them, you say he must be exterminated. Where can we poor Indians go if the government will not help us?”

Sympathetic legislators offered supportive words and promises, but as was often the case when it came to the treatment of Native Americans, the platitudes proffered by well-meaning lawmakers rarely came to fruition due to a lack of political will and opposing philosophies on how to deal with the issue. Even so, Winnemucca never gave up her crusade for justice.

Winnemucca was born in 1844 in the Humboldt Sink, about 50 miles from Reno near present-day Lovelock, Nev. She was the fourth child of Chief Winnemucca II (Jr.), head of a small Paiute band. Her parents named her Thocmetony, meaning “Shell Flower,” later anglicized to Sarah. Her maternal grandfather was Winnemucca I (Sr.), the leader of the tribe who later changed his name to Truckee. Due to her lineage as a descendant of two important chiefs, Sarah was considered a princess in tribal culture. At the time the Northern Paiute numbered just a few thousand people; they lived a semi-nomadic life and were a generally peaceful, loose-knit tribe broken into family groups.

Chief Truckee

The reason why Winnemucca I changed his name to Truckee is an interesting backstory. Phonetically the word sounds similar to “tro-kay,” which in Paiute means “all right” or “very well.” Chief Winnemucca used it frequently when steering exhausted explorers and emigrants toward the Truckee River and California. Topographical engineer John C. Frémont met Chief Winnemucca in early 1844 — followed later that year by wagon train captain Elisha Stephens and his seasoned guide Caleb Greenwood. When these men met Winnemucca I, the chief used the word “truckee” regularly to reassure them. After all, they were exposed in the wilderness and surrounded by potentially hostile Indians. It makes sense that when Winnemucca talked to them that he would say they were safe and “going to be alright” and make it to California.

Winnemucca I always counseled peace with the light-skinned newcomers. His friendly 1844 encounter with Anglos and their repetition of the word truckee made such an impression on the elderly medicine man that he changed his name to Chief Truckee. (Name revisions were common among warriors in certain tribes; they would take new names after great battles or transformative experiences.) The old chief continued using the name Truckee after Frémont commissioned him an officer while fighting with the Americans in the Mexican War. From then on, he was known as Captain Truckee until his death.

In the summer of 1846, while Sarah was still an infant, her grandfather Truckee left for California to fight with Frémont in the Bear Flag Revolt. Chief Winnemucca II, however, stayed with his people and oversaw the communal antelope hunts. Winnemucca means “the giver,” or “one who looks after the Numa (people).” It was Sarah’s father, and her supportive brother Natches who inspired her to dedicate herself to working for her tribe. But it was her grandfather’s commitment to friendship with the Anglos that galvanized Sarah’s effort to work with them despite her frustrations with the lack of progress.

Much of Sarah’s life was spent in the valley of the Humboldt Sink, a place the Paiutes referred to as a “sacred circle.” It was a time of great disruption for her people. Sarah later wrote, “I was a very small child when the first white people came into our country. They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and continued so ever since, and I have never forgotten their first coming.”

White settlers took over the choice hunting grounds and established large ranches. Herds of antelope that the Indians traditionally hunted in the higher mountains nearly disappeared. To irrigate alfalfa fields, farmers drained water from the shallow tule marsh that represented the terminus of the Humboldt River. The Paiutes had once pushed along their light reed boats hunting waterfowl in the expansive marsh, but to provide more fertile land for fields of alfalfa and grain, pioneers burned the tule growth and the bird population plummeted. The newcomers cut down the all-important piñon pines for wood, trees the Indians regarded as vital ancestral “orchards.” It takes 75 to 100 years of growth before these trees produce edible nuts.

the area

LOCAL NEWS, EVENTS AND RESOURCES

Get in touch

Curious about a neighborhood, particular property, or just have a general question?